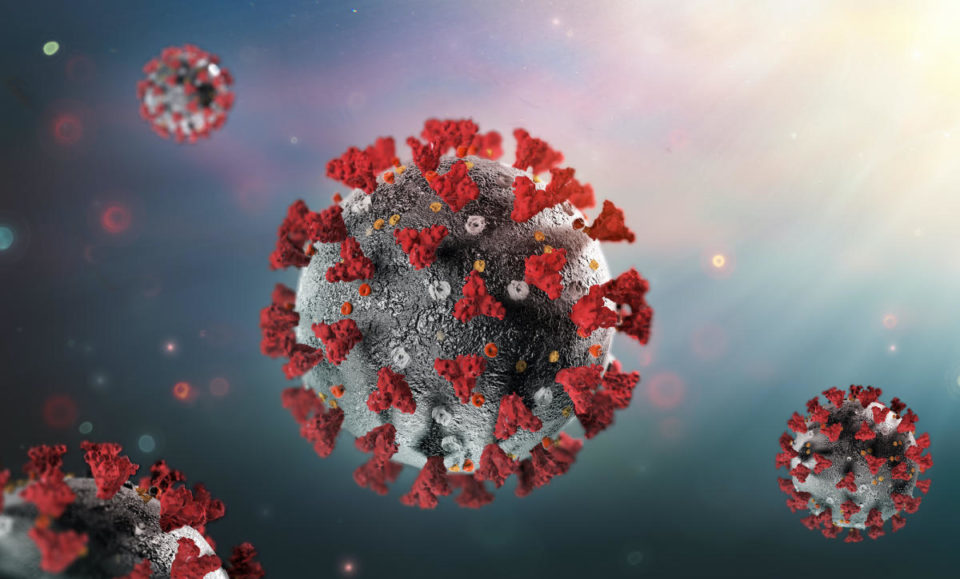

March 2020 has gone down in history as the month in which the COVID19 pandemic broke out in Western Europe. At its peak in April, half the world’s population was subjected to some form of preventive confinement.

In addition to these measures, the closing of traditional businesses meant a drastic change in consumer and social habits for several reasons: besides the necessary limitation of movement, shops admitted fewer customers and increased queues; concerned customers, specially the most vulnerable, preferred to refrain from shopping.

According to Kantar´s COVID19 barometer, 16% more Spaniards shopped online during the month of March, almost twice as many as worldwide, and between 5% and 10% Spaniards shopped online for the first time. And it seems that we will not kick the habit: 31% of those surveyed stated that they would use e-commerce more, compared to 21% who held the opposite.

Additionally, according to this analysis by HAVAS Media Group, we will shop more online although like with all changes, they will not affect everyone equally. Between 25% and a third of the people surveyed in the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy and Spain state that they will continue with these behavioral changes (35% in Spain).

35% of Spain’s population will keep these new habits.

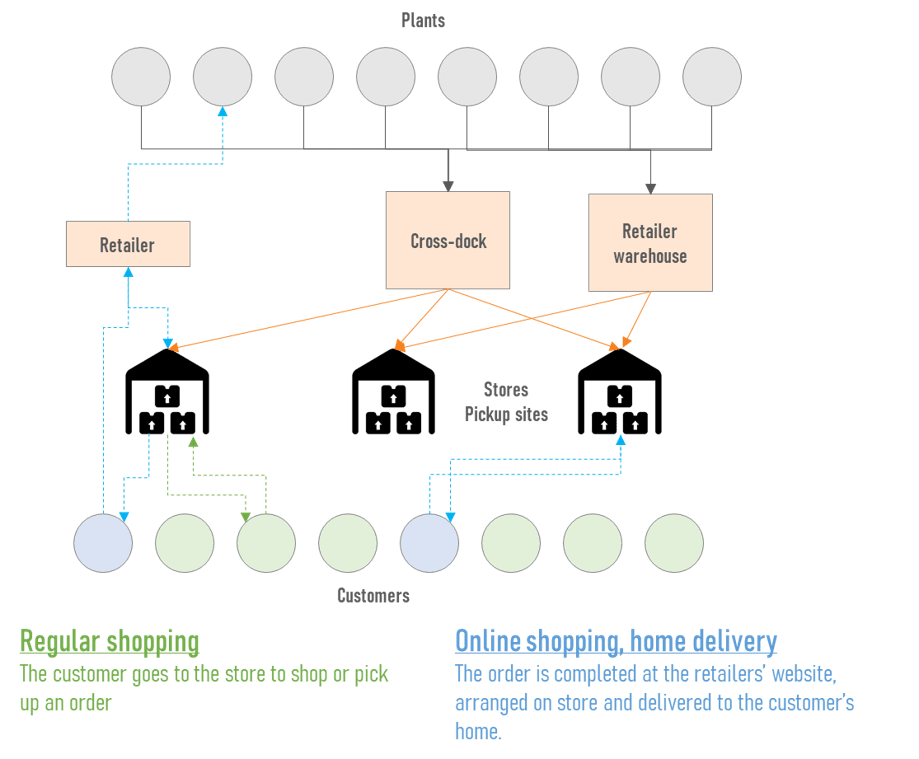

It is not surprising that the initial impact took food chains by surprise. In these, customers generally complete their orders on th retailer’s website but it is arranged and shipped from a local store. This way of organizing the online order involves a combination of cross-dock tasks, warehouse to store delivery and picking at the shop. The increase in the volume of orders, the new tasks due to the pandemics (managing queues to keep physical distance, capacity control, cleaning tasks ) and shortage of hands due to sick leaves may cause a work overload.

- Mercadona initially limited online shopping to Barcelona and Valencia

- Carrefour warned that delivery times could be extended to eleven days.

- Dia initially warned that delivery times could reach eight or nine days depending on the area.

- El Corte Inglés showed deliveries of more than one week, compared to two days before the crisis.

Aurelio del Pino, president of the Association of Spanish Supermarket Chains (ACES), which represents the supermarkets of Auchan Retail, Carrefour Group, Eroski Group, Lidl and SuperCor, declared to Expansión that “[…] it is a complex situation , supermarkets are facing such a large number of requests that they have had to resize and strengthen all their processes. “

Andreu Sánchez, head of strategy for IoT and Smart products at Cellnex: “The uncertain future evolution of COVID and new consumer habits, such as the increase in online shopping are forcing companies to evolve their processes, including logistics, and the popular Industry 4.0 enabling technologies are key to facilitating this transition.”

Ramón García, General Director of the Innovation Centre for Logistics and Freight Transport (CITET), tells us that “in the face of the expected growth in distribution through the e-commerce channel once the pandemic has passed, not only sellers will require adaptation, but also their partners in charge of last mile distribution and others involved, such as municipalities, which should seek solutions based on collaboration and shared use of resources to avoid going towards an unsustainable model in terms of cost, environmental impact and city congestion. To this end, it is very important that the standards, platforms and spaces that allow such collaboration be enabled. ”

How will it affect our logistics?

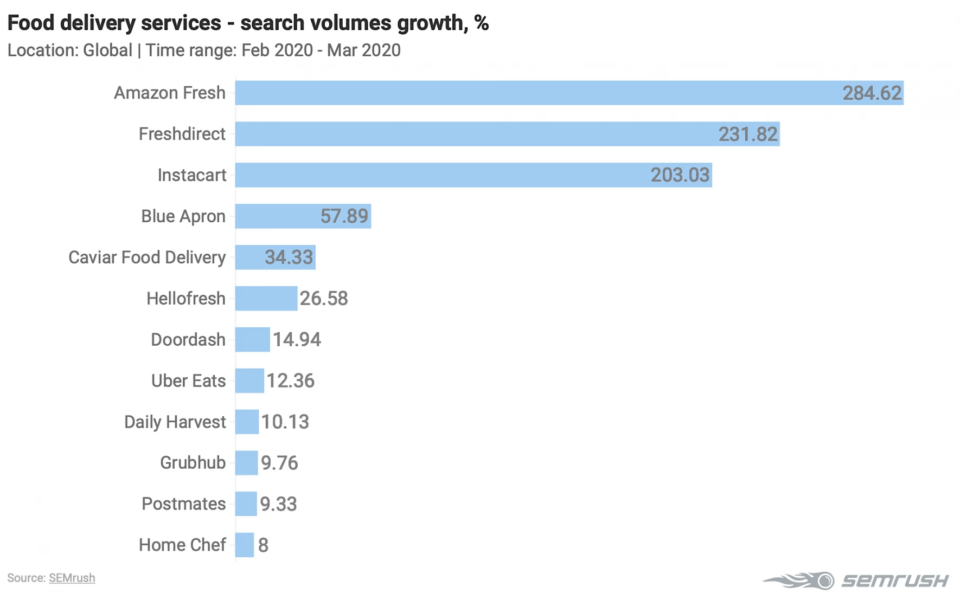

If these new habits stick, Spaniards will shop more in local and online supermarkets, and less in large stores. This may accelerate the entry of new players, such as Amazon Fresh, currently active in cities in the US and Germany, boost distribution outlets such as Glovo or Deliveroo, proximity supermarkets such as Dia and Ahorramás, to the detriment of malls like Carrefour.

This sudden change in daily shopping habits will force distribution chains to accelerate the transformation of their logistics networks to accommodate new online demand.

Traditionally, online orders are linked to stores, where they are picked up by the customers or shipped to their homes by van. As mentioned above, this means that the store must be supplied for online distribution and have resources to prepare the orders (picking).

Upstream, products are shipped from plants to shops through cross-dock centers or warehouses (logistics centers) where manual picking for stores is carried out. With this type of network, logistics tasks are performed at two different times and places: one in the warehouse for the stores (picking or cross-docking) and the other in the stores for the end customer (picking).

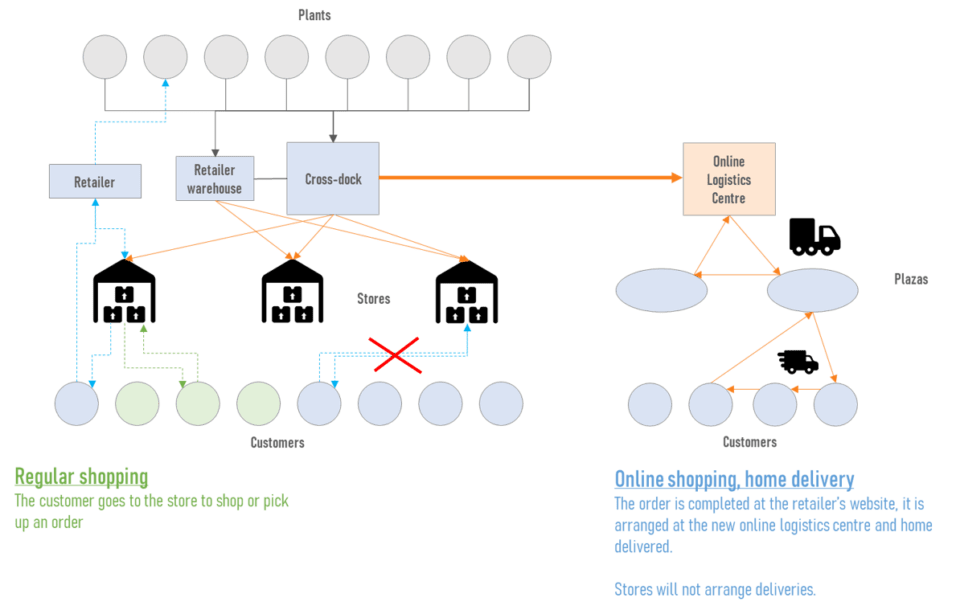

In the light of this change various alternatives are being proposed. For example, online orders can be linked to a new warehouse-supermarket near existing logistics centers where the order is arranged for the end customer. Mercadona calls these new centers “Colmenas“ (Hives), which service medium and small cities, or districts. This model eliminates one logistics activity.

Single orders are grouped by the dozens and can be shipped directly to the end customer in vans. However, when the volume of orders exceeds the van transportation capacity, it will be necessary to locate new facilities closer to the final customers in the style of the traditional plazas or squares. These squares will be stocked by trucks and vans will be waiting there in order to deliver the order to the end customer. Here the synchronicity between trucks and vans is key. Furthermore, distribution chains can form alliances with last-mile delivery companies such as Deliveroo, Glovo or UberEats, as El Corte Inglés and Carrefour have already done.

The aforementioned squares can be located in large stores or hypermarkets if the retailer has available space, or they can be shared by several distribution chains. They can be owned or managed by existing companies, new companies or even the municipalities themselves, thus taking advantage of local unused infrastructures.

In these plazas, used boxes can be collected to be transported back by truckto the warehouses for cleaning. The van, once the orders have been collected in the plaza, can take the delivery route to customers.

Thus stores can stop arranging deliveries and can concentrate in selling directly to customers.

Other solutions

Transformation is not limited to the design of the logistics network, but also to the adoption of new technologies and advanced data analytics.

Andreu Sánchez: “The personal and social disaster that COVID has brought has made the vast majority of companies react to adapt to this new reality and, in order to mitigate the negative impact, have resorted to ingenuity and technology. For example, only a few months ago, it was unthinkable that companies took a determined step towards remote work as they have been forced to now. If we focus on 4.0 technologies such as IoT, the great impact they can have on logistics is not only to facilitate process monitoring and automation, but the application of advanced analysis techniques on the large data sets it generates which combined with other data sources, provide us with behavioral predictions and other valuable information to our businesses.”

Indeed, the new data sources provided by IoT, in combination with advanced analytical techniques allow us to build forecasting and optimisation models to elevate the efficiency of the logistics network. For example: a demand forecasting model, powered by real-time data from warehouses, trailers and stores, is capable of synchronizing the flow of products, trailers and vans to ensure just-in-time supply at all stages of the network with the mathematically minimal cost.